Science Fair Takes Story to Canada

December 15, 2019

Two years ago, current John Burroughs seventh-grader Story Kummer planned and executed a science fair project that would lead to three years of research, a published article in the “Young Scientists Journal,” and a presentation at the annual Neurocritical Care Society Conference in Vancouver, Canada.

During elementary school, many students participate in science fairs that are full of baking soda volcanoes, ant farms, and the occasional vegetable battery or homegrown crystal. However, Story Kummer was no cookie-cutter fifth grader; she took her science fair experience to the next level.

During elementary school, many students participate in science fairs that are full of baking soda volcanoes, ant farms, and the occasional vegetable battery or homegrown crystal. However, Story Kummer was no cookie-cutter fifth grader; she took her science fair experience to the next level.

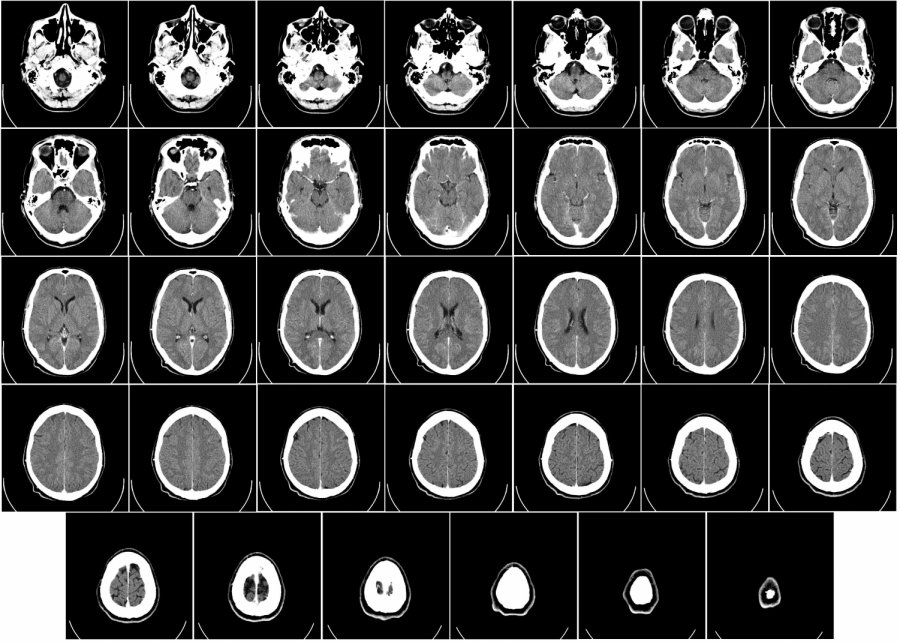

As a mere eleven-year-old, she researched whether or not artificial intelligence programs are capable of differentiating between ischemic and hemorrhagic strokes. (An ischemic stroke is when an artery in the brain is blocked, while a hemorrhagic stroke is when an artery in the brain bursts.) Kummer’s early involvement in the medical research area can be credited to her father, Dr. Terrance Kummer, a neuro-intensivist who helped her identify images of ischemic strokes and hemorrhagic strokes in the initial stages of the experiment. Dr. Kummer is also a member of the international Neurocritical Care Society; when he mentioned his daughter’s research project while talking to a coordinator of the Vancouver Conference, she was asked to open the conference with a short presentation of her research.

“Is artificial intelligence capable of being trained to tell the difference between ischemic and hemorrhagic strokes?”

— Story Kummer

Kummer’s research question was, “Is artificial intelligence capable of being trained to tell the difference between ischemic and hemorrhagic strokes?” She used Google’s teachable machine software, available to anyone online, as the basis of her project. Then she found images of both types of strokes that had been taken during CT scans and had her father review the images to ensure accuracy. The software was given many images of the two different strokes and at first was told which image was which type of stroke. Over time, the artificial intelligence would be trained to associate the given images with one type of stroke and identify it without human input. Finally, she tested her program by introducing new images to the software and asking it to identify which type of stroke was depicted.

Kummer’s experiment had a seventy-four percent success rate, and she hopes to improve upon that by training the software with more images to reduce the margin of error during her time here at Burroughs. Kummer’s stroke-detecting artificial intelligence, at the very least, seems likely to have taken first prize in any fifth grade science fair.